Therapy halfway through

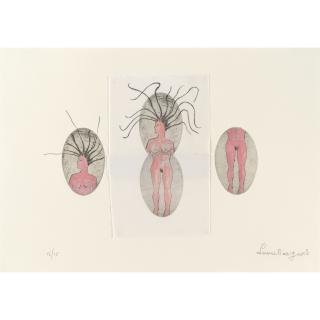

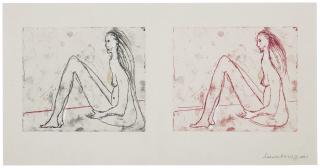

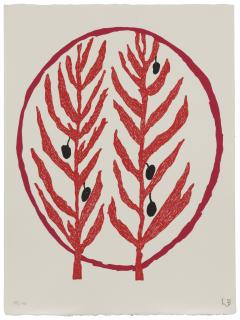

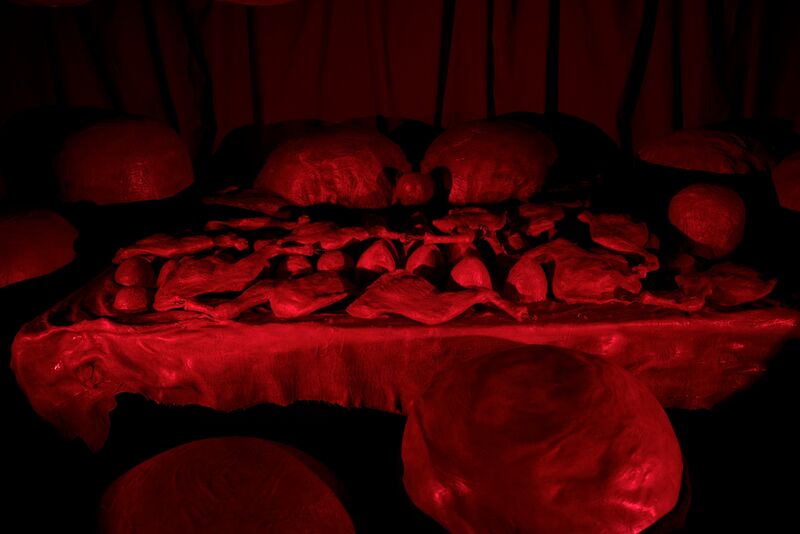

The Cells combined with the spider-shaped works to form her life's work. Before Louise Bourgeois solidified her modus operandi, however, she created predecessor models of her small rooms, the Cells, lots of sculptures, and performance art. Bourgeois produced three significant works in the middle of her life: Janus Fleuri (1968), The Destruction of the Father (1974), and A Banquet/A Fashion Show of Body Parts (1978). They illustrate that she created art to find shelter and come to terms with the profound conflicts of her childhood. The New Yorker described in 2002, shortly after her 90th birthday, that fear was the main theme of her work, but anger was a close second. The paper references an older interview in which Bourgeois is reported to have said that she takes a »fantastic pleasure in destroying everything.«