More on the subject Artist Portraits

»Photography is my work - watercolors are my pearls.«

With city views of Berlin, Efraim Habermann became known to a broad public as a photographer in the 1960s. His works are characterized early on by a distinctive, concise style and unusual perspectives. Today, after a 50-year creative phase, he has an extensive body of photographic work, consistently in black and white, with numerous series from Israel, Venice and Berlin, still lifes, portraits and photographic collages. Habermann's »pearls«, his mostly constructivist watercolors, geometric forms in strong colors, finely balanced into a postcard-sized composition, seem almost like a commentary on his own conception of the image. An extensive exhibition of works from the artist's private archive can now be seen in Berlin from mid-February.

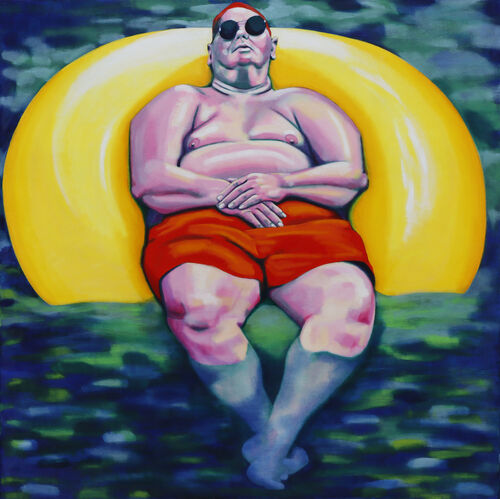

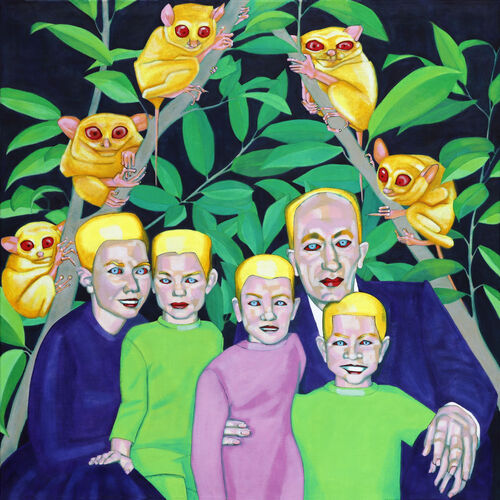

The world in pastel

With simple portraits and landscapes in pastel, the Swiss painter Nicolas Party succeeded in rising to the top of the art league. The former graffiti artist captivates with universal themes and used the pandemic for monumental projects.

Dive deeper into the art world

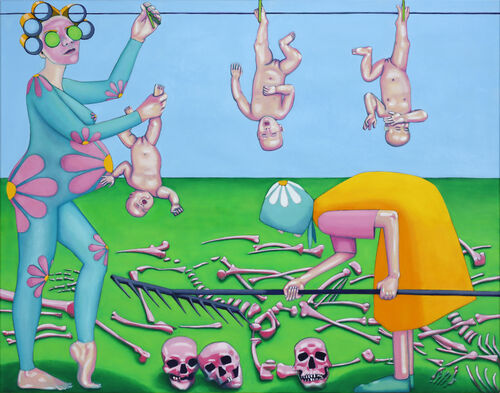

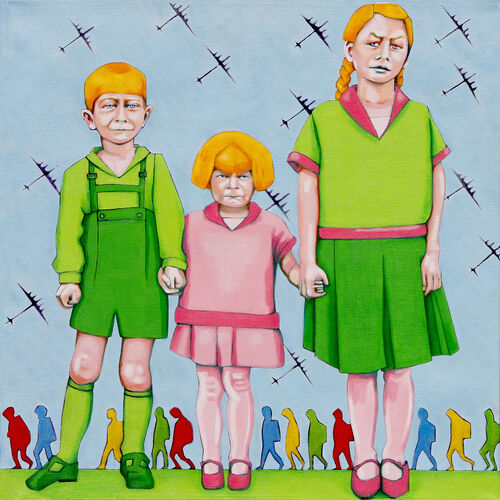

Identity in a social context

Matthew Eguavoen portrays people with a strong personality and a fixed gaze. Depicted against a reduced background, the social context is kept deliberately hidden, making it a subject for discussion. Eguavoen challenges the observer to speculate about the living conditions, experiences and characters of the people depicted, and takes them into uncertain terrain. A young artist from Nigeria with his own signature, whose paintings deal with the central question of origin and identity.